Full Scale Audiovisual System Use

This week, I welcomed Lauren Sherlock back into the studio to help me experiment with the newly developed visual-sampling techniques using full-scale projections. Working in-situ in a larger studio allowed us to experiment with a wider range of movements and explore interactions between the performer and the projections. The session helped me identify areas for optimisation within the system, its relevance to interaction discourse and the advantages of certain compositional options. However, the greatest result of the session was discovering the incredible potential for improvisation that the system revealed when the auditory and visual elements were combined.

The recording of the session below features three highlights stitched together. Elements displayed include the point-cloud rendered body visualisation with sequenced visual samples and a two-dimensional body outline feeding back into a Cache TOP, resulting in the visual delay. Sonic control can be heard in the timbre of the harmonic resonator, while the chord changes and drum samples are all sequenced within the modular. The drum sequencer is doubled to also control the visual sampler as described in the previous post.

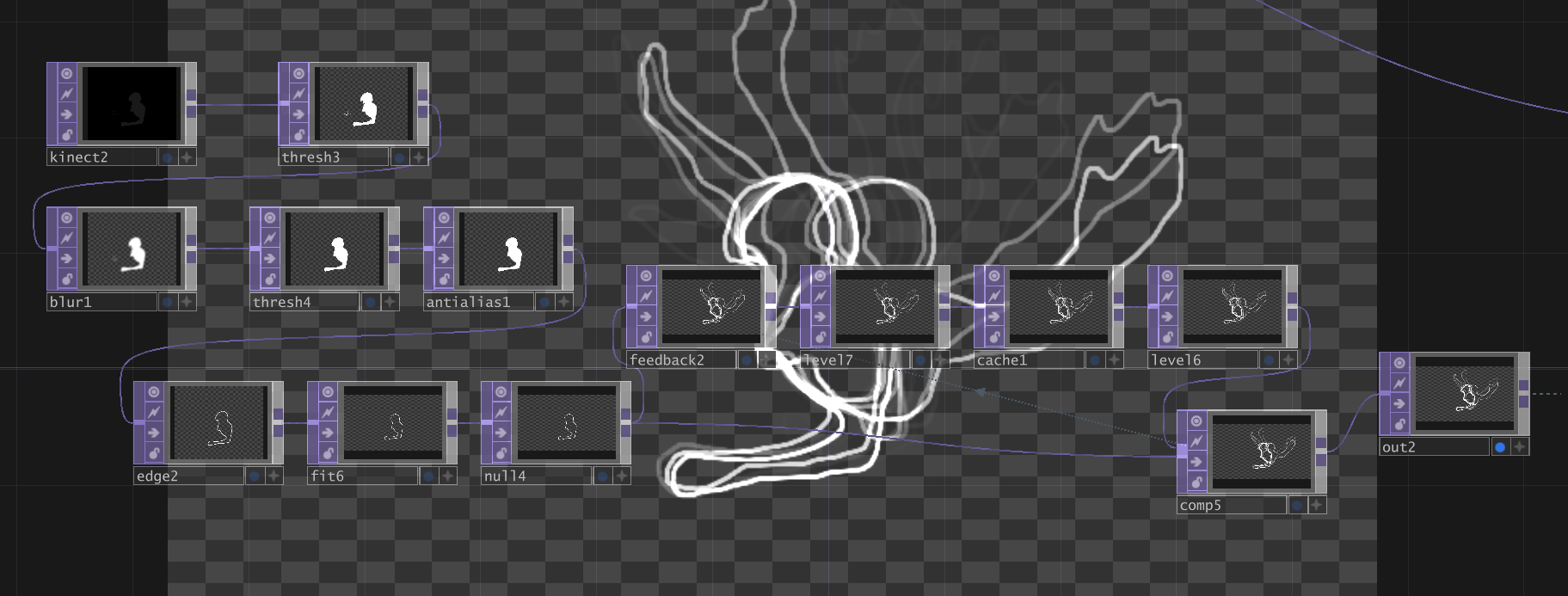

Beginning with the back end, this was the first time I had combined the various Touchdesigner networks for sound control and body visualisation into one multi-layered Touchdesigner project. Though there was a drop in frame rate, the software remained functional and relatively stable. The only significant strain on the system came from the use of Cache TOPs, predominantly the two-dimensional outline visualisation. As the Cache TOP is positioned within a feedback loop, the memory used seems to increase. Limiting the duration of the video recorded in the cache by adding a level with reduced opacity to the feedback loop seemed to lighten the load, however restarting the TOP or the software was required on more than one occasion. I took several notes throughout the session of possible ways to optimise the Touchdesigner project, including reducing Base layers, mapping MIDI controller buttons to turn cooking on/off for bases depending on when they are needed and passing over networks to delete unused nodes.

The two-dimensional body outline visualisation network with feedback cache, causing the visual ‘echo’ seen around the body.

Confronted with so much new possibility, it was difficult at first for Lauren and I to know where to begin compositionally. In the last sound-focussed session we were able to repeat a series of movements and discuss the sonic control as we went, whereas in this case the addition of full scale projection felt somewhat overwhelming. However, as we used the system we were increasingly able to de-intellectualise the process and reach an area of total improvisation, resulting in the clips featured above. The incredible sensory satisfaction of using the system proved powerful enough to fuel hours of engaged improvisation. Lauren stated at one point “I could do this for hours”.

As the session progressed and the improvisation became even more fluid, compositional discussion became more readily available, but in a different way. Rather than consisting of specific movement phrases or sonic devices, were found ourselves employing much more vague terms concerning energy, pace, range and speed. As the mediums increased, so our language had to change into vocabulary that could span sound, movement and image. Working in-situ, these concepts could be bolstered by their immediate demonstration rather than coherent discussion. As I reflect more on this experience, I see that what we were dealing in was embodiment, or pre-cognitive ideation - terms deeply embedded in HCI discourse. In ‘Understanding the Role of Machine Learning in Movement Interaction Design’, Marco Gillies (2019) traces the concept of ‘embodied knowledge’ through the works of Atau Tanaka (2013) and Merleau Ponty (2002) to contribute to his framework for describing movement interaction. Likening embodied knowledge to knowing how to ride a bicycle, Gillies draws on Tanaka to highlight the pre-cognitive nature of the phenomenon and the difficulties one encounters when articulating it. While I have severely simplified the discussion here, the point is that Gillies stresses how the concept of embodied knowledge is extremely relevant to understanding movement interaction. As my work is approaching stages of refinement, I am discovering this all too well. I am becoming sensitive to where conceptual grounding is needed and being spurred to revisit concepts as they are contextualised within the system. For these final weeks, a revisiting of writers like Gillies may be a great place to start.

Through this kind of reflection-in-action experimentation, we found several audiovisual devices that might become building blocks for a composition. These included various mixes of the two body visualisations, repositioning of the two-dimensional visualisation (eg. mirrored above the body), removing the live-feed visualisation to feature only the visual sampler and various ways the visualisations may influence movement sequences. Most notably of the final device was the use of the two-dimensional visualisation, as the feedback delay of the outline enabled Lauren to construct new and intriguing shapes through movement sequences. This is featured in the early parts of the clip. In the visual sampler, the most notable finding was that sequencing the recording phases of the sampler as well as the play phases made for the most engaging performance of the device, as body movements were recalled in real time, rather than specific frames being repeatedly recalled to become quickly tiresome. This is displayed in the latter half of the clip.

Finally, this holistic experimental experience was somewhat tough to reflect on in its entirety. It was very fulfilling to see all the elements in action together and freeing to have another body to use the system while I programmed. However, as this project is looking at expanding my own performance practice, I must re-focus the techniques on how they might adorn a single performer. I also feel that the point of refinement is approaching - at some stage I must stop adding elements to determine when they’re most appropriate. But, then again, we haven’t even touched audio-reactivity…